She was only three months old when her life ended in one of the most horrifying crimes Ohio had ever seen.

Her name was Janiyah Watkins, and in the spring of 2015, her name became a wound that a whole community would carry.

Not because anyone wanted to repeat it—but because forgetting felt like another kind of cruelty.

It was March in Hamilton County, the season where winter loosens its grip but the air can still feel sharp in the lungs.

The neighborhood looked like so many others—trim lawns, quiet streets, porch lights that flicked on at dusk, and homes where life happened behind curtains.

On the morning police were called, nothing about the outside of the house suggested a nightmare was waiting within.

A few cars sat in driveways.

A trash bin near the curb.

The kind of ordinary details that make tragedies feel even more unreal when they erupt.

A 911 call came in, and officers responded to the suburban home with the usual urgency of first responders who know that seconds matter.

They walked toward the front door expecting… something.

They never expect what they actually find.

Inside, the scene stopped them cold.

Baby Janiyah was found lifeless on a kitchen counter.

She was so small that the word “baby” didn’t fully capture it—she was still newborn-soft, still in the stage of life where her entire world should have been arms and warmth and milk and sleep.

Instead, she was gone.

The details were so disturbing that even seasoned officers struggled to describe what they saw.

There are images the mind can compartmentalize, and then there are images that break through every wall a person has built to protect themselves.

For some responders, that kitchen would become the place they revisited in nightmares for years.

The name attached to the horror was one no one wanted to say aloud: Janiyah’s mother.

Deasia Watkins was 22 years old.

Young enough to still be figuring out her own life, and yet already carrying the immense, relentless responsibility of motherhood.

And according to those who knew her story, she was not simply a cruel person who did a cruel thing.

She was a young woman battling severe mental illness.

Postpartum psychosis.

A condition that can tear reality apart so violently that the mind no longer recognizes what is real, what is safe, what is right.

It is rare, it is dangerous, and it is often misunderstood until it is too late.

In the days leading up to that morning, the system had already been involved.

Child services had removed Janiyah from Deasia’s care, placing the baby in the custody of an aunt who was meant to keep mother and child apart—at least until Deasia could be stabilized, monitored, treated.

That decision had been a recognition that something was wrong.

A recognition that Deasia’s state of mind made her unsafe to be alone with her infant.

But recognition is not the same as protection.

Not when resources are thin.

Not when families are stretched.

Not when supervision can’t be perfect twenty-four hours a day.

Somehow, that morning, Deasia gained access to the home where her daughter was staying.

How it happened—through a door left unlocked, through a moment of trust, through the complex messiness of families and systems—is the kind of question people ask again and again, hoping to find a single point where things could have changed.

But tragedy rarely has just one crack.

It has many.

And then it happened.

What followed defied reason, an act of violence so extreme that many people could not speak about it without their voices shaking.

The kind of crime that becomes shorthand for horror, and yet, in this case, it also carried the terrible shape of illness.

When the news spread, it hit Hamilton County like a shockwave.

People who had never met Janiyah cried as if they had.

Parents looked at their own babies with a sudden fear they couldn’t explain.

Neighbors stood in driveways whispering, asking the same question over and over:

How could this happen?

The question sounded like anger.

It sounded like grief.

It sounded like disbelief.

It also sounded like a desperate search for control.

Because if you can understand something, you can believe it won’t happen to you.

But some tragedies refuse to be contained by understanding.

Postpartum psychosis is one of those realities that exists like a storm.

It can arrive fast.

It can distort perception completely.

It can create delusions so convincing that the person living inside them cannot hear the voices outside.

For many families, postpartum mental health is discussed in terms of sadness, exhaustion, and anxiety.

Important conversations, yes.

But postpartum psychosis is different in severity and urgency.

It can include hallucinations, paranoia, disorganized thinking, and a disconnection from reality that can become life-threatening if not treated quickly and intensely.

Those who later spoke about Deasia said she wasn’t herself.

That she had been showing signs.

That she needed help.

But needing help and receiving it are not always the same thing.

There is a gap in many communities—between recognizing mental illness and responding with enough resources to prevent catastrophe.

There are long waits, underfunded programs, overwhelmed hospitals, and families who don’t know how to navigate the system until they are drowning.

And when the person in crisis is a new mother, the stigma can be suffocating.

Some women are afraid to admit what they are experiencing, terrified of being judged, terrified of losing their children, terrified of being labeled monstrous when they are actually ill.

In Deasia’s case, the system did intervene—child services removed the baby.

But the intervention came with a brutal reality: separation alone does not treat psychosis.

It can even worsen it, depending on the delusions involved.

Treatment requires psychiatric care, medication, monitoring, and a net of support that is both medical and human.

The morning Janiyah died became the kind of moment that rewrites a community’s sense of safety.

It wasn’t a random street crime.

It wasn’t a stranger in the dark.

It was inside a home.

Inside a kitchen.

Inside a family.

That is why it hurt differently.

Because the place that should have been safest became the site of the worst thing imaginable.

In the weeks and months after, the case moved into the legal system, where horror is translated into charges.

Where life is reduced to documents.

Where grief sits in the back of a courtroom while lawyers speak in careful terms.

The public response was intense and divided.

Some people demanded only punishment.

They wanted a sentence that matched their outrage, because outrage was the only emotion that made the world feel less helpless.

Others, including mental health advocates, insisted that the story had to include illness.

Not as an excuse—but as a warning.

As a reason to look harder at postpartum mental health and the gaps in care.

Two truths can exist at once:

A child’s life was taken in an unforgivable act.

And the person who committed it was deeply, dangerously unwell.

Holding both truths is difficult.

It requires nuance in a world that often prefers simple villains and simple answers.

In 2017, Deasia Watkins pleaded guilty to murder.

The court sentenced her to 15 years to life in prison.

A sentence that acknowledged the gravity of the crime while allowing for the complex reality that her mental state was central to what happened.

Her defense argued she wasn’t herself.

That she had lost touch with reality.

That she needed psychiatric help, not hatred.

For many, the case became one of heartbreak more than horror.

Because horror alone suggests a monster.

Heartbreak suggests something more tragic: a life destroyed by illness, and another life ended because illness was not caught in time.

But heartbreak does not make the pain softer.

It only makes it more complicated.

Because baby Janiyah did not get a chance to grow.

She did not get a chance to laugh, to toddle across floors, to say her first words, to become a person whose personality would fill a room.

Her whole life was supposed to be ahead of her.

Three months is such a short time.

It is barely enough time for a baby to recognize a voice, to settle into a rhythm, to be held and fed and rocked into the world.

And yet, in those three months, she became loved.

Someone bought her tiny outfits.

Someone kissed her cheeks.

Someone watched her sleep and thought, You’re here. You’re real. You’re mine to protect.

That is what makes it unbearable.

In the quiet neighborhood where it happened, the house became a symbol.

Not because anyone wanted it to be, but because places absorb history.

People drove past and slowed down, feeling a chill even on warm days.

Some neighbors moved away.

Some stayed and tried to reclaim normalcy.

But the story didn’t leave easily.

It lingered in conversations, in news anniversaries, in the way parents talked about postpartum depression with a new urgency.

Years later, the case still carried echoes.

It forced people to confront the uncomfortable reality that a mother can be both a caregiver and a danger if she is psychotic and untreated.

It forced the question of how society supports new mothers—how often they are left isolated, overwhelmed, and ashamed to admit they are losing control.

It also forced a question about systems designed to protect children.

If the baby had been removed days earlier, how did access happen?

Was there a failure in supervision?

A failure in communication?

A gap in emergency response planning?

These questions mattered because they were not only about blame.

They were about preventing the next tragedy.

When a case becomes a lesson, the lesson is often learned in blood.

That is the cruel trade.

Mental health advocates pointed to Janiyah’s story as a reason to treat postpartum psychosis like the emergency it is.

To train healthcare providers to recognize warning signs quickly.

To ensure new mothers have access to psychiatric evaluation without stigma.

To provide crisis support that does not end at a referral list.

Families needed support too.

Because family members are often the first to notice that something is wrong.

They are also often the least equipped to know what to do next.

What do you do when someone you love is speaking in delusions?

When they seem paranoid, disorganized, frightened?

When they insist something terrible is true when it isn’t?

If you call for help, you fear the consequences.

If you don’t call, you fear worse.

This is the trap many families find themselves in.

And in some cases, as with Deasia, the trap snaps shut before anyone can escape.

None of this brings Janiyah back.

Nothing makes her death anything less than devastating.

But memory can still be an act of care.

Remembering Janiyah means speaking her name gently, not as a headline but as a child.

It means acknowledging that she deserved to grow.

It means recognizing that postpartum psychosis is not a moral failing—it is an emergency illness requiring immediate treatment.

And it means admitting that systems can see warning signs and still fail to catch someone before they fall off the edge.

Years after the sentencing, people still struggled to hold the story in their minds.

Some could only feel anger.

Some could only feel sadness.

Many felt both.

Because the case sits at the intersection of two unbearable realities:

a baby’s death, and a mother’s mind lost to illness.

Janiyah was only three months old.

The warning signs were there.

And help arrived too late to save the one life that mattered most.

In the end, a quiet suburban home became a symbol of what happens when mental illness meets isolation and inadequate crisis support.

A kitchen counter became an image no community should have to carry.

And baby Janiyah’s name became a reminder—of innocence, of loss, and of the urgent need to treat postpartum psychosis with the seriousness it demands.

If there is anything the story leaves behind, it is this:

Compassion and accountability are not enemies.

A society can grieve a child fiercely and still demand better care for mothers in psychiatric crisis.

Because protecting children means protecting the people who care for them, too—before illness turns into tragedy, and before a brief life becomes nothing but an echo behind closed doors.

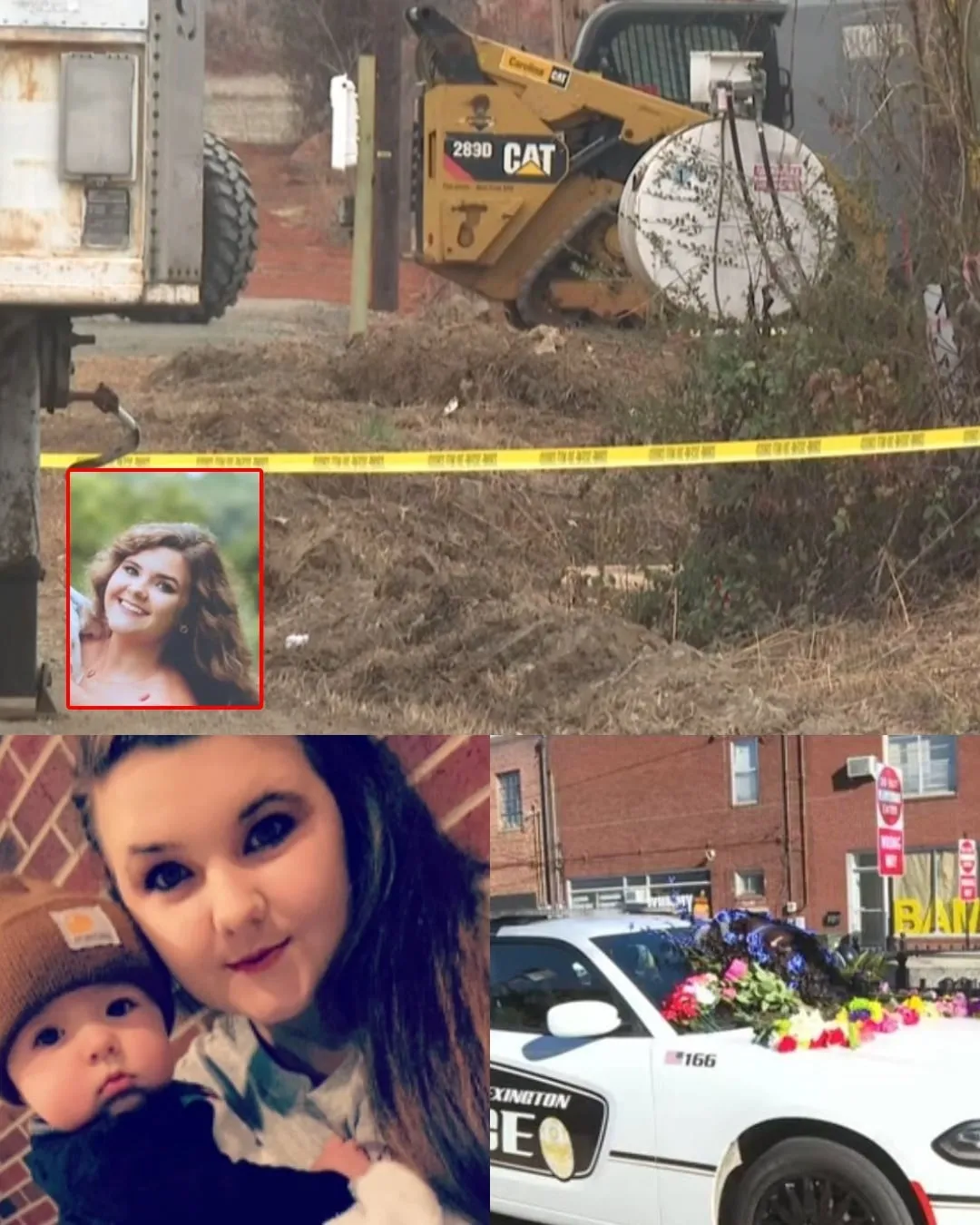

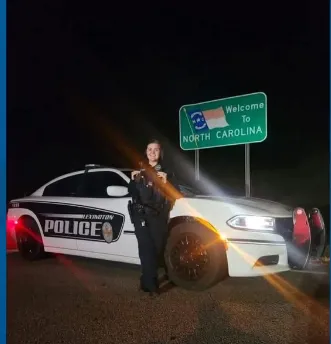

Lexington Mourns: Remembering Officer Kaitlin “Katie” Crook.5870

The news reached Lexington in the quiet, stunned way that tragedies often do—first as a whisper, then as a sentence no one wanted to finish.

An off-duty police officer had been shot in a parking lot.

She was only twenty-five years old.

Her name was Kaitlin Crook, though almost everyone who loved her called her Katie.

She wore the uniform with pride, carried herself with calm strength, and believed deeply in protecting the community she called home.

On December 17, that life was taken, leaving behind grief that rippled far beyond the scene where it happened.

The shooting occurred while Katie was off duty, in a place that should have felt ordinary and safe.

Two other men were wounded in the same incident, a violent collision of lives that investigators say involved people who knew one another.

The North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation stepped in, working carefully to piece together the truth behind a moment that changed so many lives forever.

For Lexington, this was not just another headline or police report.

This was one of their own—a young woman many had watched grow, train, and commit herself to service.

The loss settled over the town like a heavy fog, making even familiar streets feel unfamiliar.

Katie was more than a badge number or a uniform folded with care.

She was a daughter whose parents spoke of her strength with pride and heartbreak intertwined.

She was family, friend, protector, and presence—someone whose laughter and determination left marks that cannot be erased.

Those closest to her remember a young woman who faced challenges head-on.

She believed in showing up, even on the hardest days, and in standing firm when others felt afraid.

To them, her courage was not something she switched on at work—it was who she was.

In the police department, the loss struck with particular force.

Officers train for danger, prepare for worst-case scenarios, and accept risk as part of the calling.

But no amount of training softens the blow when one of your own is taken too soon.

Colleagues described Katie as focused, disciplined, and deeply committed to learning her craft.

At just twenty-five, she had already earned respect from peers who saw in her a future leader.

Her death left unanswered questions—not just about the investigation, but about the years she never got to live.

Outside the department, residents struggled to process the reality of what had happened.

People left flowers, candles, and handwritten notes—small offerings meant to say what words could not.

In quiet moments, strangers stood together, united by shared grief.

Parents hugged their children a little tighter.

Friends checked in on one another with messages that said, “I’m thinking of you,” even when they didn’t know what else to say.

A community learned, again, how fragile safety can feel.

As investigators continue their work, officials have been careful with details.

The facts matter, and the truth deserves patience and clarity.

But for those grieving, answers—when they come—will never restore what was lost.

Katie’s family has spoken publicly with remarkable grace in the face of unimaginable pain.

They described a daughter who was strong, loving, and devoted to the people around her.

Their words carried both pride in who she was and devastation over who she will never become.

Grief, in moments like this, is not quiet.

It arrives in waves—sometimes as tears, sometimes as anger, sometimes as silence that feels too loud.

For Katie’s parents, siblings, and loved ones, every day now carries the weight of absence.

Plans have been made to honor her life.

A public visitation and funeral service will allow the community to gather, to remember, and to say goodbye.

Uniforms will be pressed, badges shined, and flags lowered in solemn respect.

Law enforcement agencies from near and far have offered condolences.

Messages of support have poured in, reminding the family they are not alone in their sorrow.

In shared grief, there is also shared solidarity.

During the service, there will be stories.

Stories of training days, of laughter, of moments when Katie’s resolve inspired others.

Stories that keep her human, vibrant, and present—even in loss.

Her death also forces difficult conversations.

About violence that spills into everyday spaces.

About the cost borne by those who choose to serve, even when they are off duty.

Katie did not expect to be remembered this way.

She likely imagined a future filled with growth, experience, and long years of service.

Instead, her legacy is now carried in memory and meaning rather than time.

For young officers watching from the sidelines, her story is both heartbreaking and sobering.

It is a reminder that the badge does not come with guarantees, only responsibility and risk.

Yet it also highlights the courage required to step forward anyway.

Lexington will move forward, because communities always do.

But it will do so changed, carrying the knowledge of what was lost.

Katie’s name will not fade easily from conversations, classrooms, or patrol briefings.

In the coming months, the parking lot where the shooting occurred may look ordinary again.

Cars will come and go, footsteps will pass through without pause.

But for those who know, that place will always hold a shadow.

Grief does not follow a schedule.

It lingers long after headlines move on and public attention shifts elsewhere.

For Katie’s family, the real work of mourning is only beginning.

They will grieve the milestones she will never reach.

The birthdays, the promotions, the quiet moments that should have come with age.

Each one a reminder of a future cut short.

And yet, even in sorrow, there is remembrance.

There is the choice to speak her name, to tell her story, to honor her values.

There is the commitment to ensure her life meant something beyond the tragedy of her death.

Katie Crook served her community with integrity and resolve.

She lived as someone who believed in showing up for others.

That is how she deserves to be remembered.

As Lexington mourns, it also stands together.

In shared silence, in folded flags, in candlelight and prayer.

A town holding space for a young officer whose light went out far too soon.